From the Prologue

Once Upon a Time in Egypt

Eight-thousand-year-old pictographs found in the Cave of the Swimmers at Wadi Sura, in the southwest Egyptian desert. (Roland Unger, altered to black & white)

From the Prologue

Once Upon a Time in Egypt

Eight-thousand-year-old pictographs found in the Cave of the Swimmers at Wadi Sura, in the southwest Egyptian desert. (Roland Unger, altered to black & white)

Fifty years ago this Monday at Kent State University, four students were killed and nine wounded when National Guardsmen fired on protestors during a mid-day rally to protest the Vietnam War and the Guard’s occupation of the Kent State campus. What happened that day was an American tragedy — for the students, of course; for the Guardsmen, who were terribly led; and for the University, whose administration went missing in action at the critical moment. All the toxic waters of the 1960s flowed together at Kent State that weekend, in the worst possible way and with a terrible outcome. Writing 67 Shots: Kent State and the End of American Innocence broke my heart time and again.

Fifty years ago this Monday at Kent State University, four students were killed and nine wounded when National Guardsmen fired on protestors during a mid-day rally to protest the Vietnam War and the Guard’s occupation of the Kent State campus. What happened that day was an American tragedy — for the students, of course; for the Guardsmen, who were terribly led; and for the University, whose administration went missing in action at the critical moment. All the toxic waters of the 1960s flowed together at Kent State that weekend, in the worst possible way and with a terrible outcome. Writing 67 Shots: Kent State and the End of American Innocence broke my heart time and again.

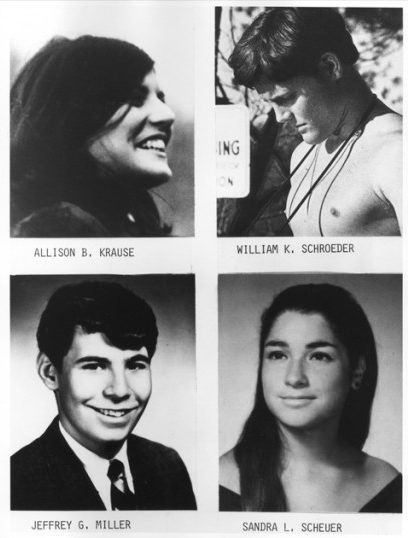

Please take a moment Monday to remember the dead: Allison Krause, Jeffrey Miller, Sandra Scheuer, and William Schroeder. And also please keep in mind what Janice Marie Wascko, who was one of the students protesting that day, told me: “If there’s no forgiveness, there’s no healing, and the murder goes on forever.”

I’ll be talking about the Kent State shootings on C-SPAN’s Washington Journal Sunday morning, beginning at 9 a.m. ET.

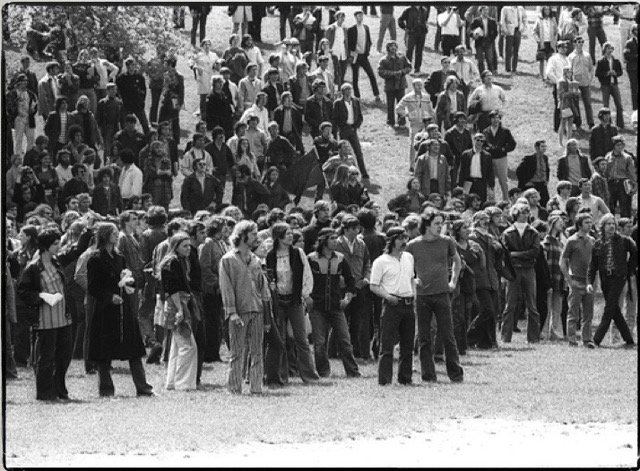

Author Howard Means talks about the tragedy that transformed America. Thirty to fifty serious protesters were surrounded by thousands of curious onlookers and students walking between classes. Over 1,300 National Guardsmen, 138 military vehicles, seven armored personnel carriers, three tanks adapted with mortar launchers, five armored command vehicles, 13 helicopters, and four fixed-wing aircraft had been dispatched by Governor Rhodes, who was in a race for the U.S. Senate. The ill-trained and improperly equipped Guardsmen were led by zealous commanders who had no tolerance for hippies and communists. Four people died, and nine were wounded. Some were almost three football fields away from the Guardsmen. The shooting was tragic, but the ensuing cover-up and misinformation was equally tragic. The media failed to report accurately, and the community and the nation never got the full story. Richard Nixon, according to Chief-of-Staff John Haldeman, was always strange, but Kent State started him down “the tunnel of the weird”. Listen to this amazing story.,

Q. Let’s cut to the chase. What happened on May 4, 1970, at Kent State?

A. There are various ways to look at it. One is that all the violent, dissonant, discordant forces of the 1960s arrived at the same time on one university campus in northeast Ohio. Another is that the May 4 shootings were, in a sense, collateral damage to the political ambitions of then Ohio Governor Jim Rhodes. Either way or whatever way you look at it, the bottom line is the same: four dead, nine wounded, and a lot of other lives, Guardsmen and students, scarred for years to come.

Q. How about the triggers? What brought this on?

A. Richard Nixon’s April 30 announcement that the Vietnam War was being extended into Cambodia. The first warm weekend of the year on a college campus that had been wrapped in winter dreariness for far too long. Youthful spirits. Rising sap. Bursting hormones. Cheap beer. Townspeople increasingly shocked by and distrustful of the neighboring college campus that was their economic lifeblood. Rumor mongering. Criminal acts by a relative fistful of students. A burned-down ROTC building. National Guardsmen ill-trained and ill-equipped for the job they were called to do. Weak leadership all around. It’s not a take-your-pick situation. They all played a role in the horror to follow.

Q. But if you had to pick one factor over all the others?

A. If I absolutely had to pick, I would lay the greatest share of the blame at the feet of Jim Rhodes. He couldn’t succeed himself as governor, so he set his sites instead on the US Senate seat being vacated by Stephen Young. The Friday before the shootings, Rhodes was trailing Robert Taft Jr. by roughly 70,000 votes in the Republican Senate primary. Saturday night, when the ROTC building burned and Rhodes sent the National Guard into Kent, the two candidates had their last debate, and Rhodes pressed his law-and-order credentials hard, as Ronald Reagan had been doing so successfully in California. Sunday morning, at a press conference in Kent, Rhodes promised to “eradicate the problem, not treat the symptoms,” irresponsible rhetoric that came horribly to life on Monday when the Guardsmen opened fire and Kent State found itself splashed all over the national headlines. And by Tuesday, when the primary vote was held, Rhodes had made up 65,000 votes of that 70,000 deficit. The weekend riots at Kent State were a godsend to Jim Rhodes. He did everything he could to exploit the situation, and the strategy damn near worked for him.

Q. How about President Nixon?

A. Nixon, the White House, the Vietnam War — they are all the background music to May 4. For that matter, so are Jack Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. But that soundtrack had been playing for a long time by the spring of May 1970, and nothing close to this had ever happened before. Besides, by the morning of May 4, Vietnam itself was the background music to something far more personal to Kent State students — the complete takeover of their campus by the Ohio National Guard.

Q. One last question, why write about Kent State now, going on 46 years after the fact?

A. That’s a good question. Believe me, I asked myself that many times as I was starting into writing this book. But if we don’t learn from the past, we are condemned to repeat it, and I think the evidence that we haven’t adequately processed Kent State into the national dialogue and memory is everywhere around us. What happened at Kent State? A civilian disruption — rioting (or semi-rioting, to be more exact) students — was coupled to a military solution — M1 battle rifles, bayonets, tear gas — with disastrous results. The equipment is far more advanced these days, but that same scenario keeps getting played out in Ferguson, Missouri, in Baltimore, and in so many other national hotspots.

This book was in many ways a tour through sorrow — the sorrow of the 120-plus oral histories I drew upon, the sorrow of the dozens of people I interviewed in my effort to understand the events of May 4, 1970 — but to me the greatest sorrow of all can be found in the after-action report filed by the National Guard’s ranking officer at Kent State, Brig. Gen. Robert Canterbury. “Problems Faced and Lessons Learned?” the questionnaire asks, along with “Recommendations.” Beside both, Canterbury had penned in “None.” We need to learn that with civilian dissent, more firepower is seldom if ever the answer. That’s what Kent State should have but failed to teach us.

from the April 13, 2015, VARIETY:

George Clooney and Grant Heslov’s Smokehouse Pictures has picked up the film rights to Joe Navarro’s “Three Minutes to Doomsday.”

The book follows the FBI’s leading body language expert, Navarro, who was sent to track down Rod Ramsay to report on his knowledge or association with Clyde Lee Conrad, an U.S. Army officer who sold top-secret classified information to the People’s Republic of Hungary. It documents Navarro and Ramsey’s relationship and interviews against the backdrop of the Cold War.

Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, recently acquired North American rights for the book.

Howards Means, who collaborated with Robert Baer on “See No Evil” and “Sleeping With the Devil,” assisted Navarro in his writing. “Syriana,” for which Clooney won an Oscar, was based on Baer’s books.

Sultana: The Novel opens in early April 1865 inside the Confederate prison at Cahaba, Alabama. The central characters initially are four Union soldiers from Muncie, Indiana — two brothers, their uncle, and a best friend — who had been captured while trying to round up mules. Soon, they are joined by a mute boy who appears almost by magic inside the prison. Within weeks, the war ends, and the men are released, but their travails have only begun. By steamer, rail, and mostly by foot the four “Muncie men,” now five with the boy, and their fellow ex-prisoners are conveyed to Vicksburg, Mississippi, to await passage up river to Camp Chase, in Ohio, where they will be mustered out. Their horrible fortune is to be sent north on the Sultana.

The novel mixes fiction with fact, real figures with imagined ones. For years, I tried to tell this story as a straight history but could never get it right to my satisfaction. Only when I invented these five people could I make the history come alive in my own mind. My hope is that they will bring this great and needless tragedy to life for you, too.

I should add that I am giving this book away free for two reasons: I’m currently writing a look back at the May 4, 1970, shootings at Kent State University and have a clause in my book contract that forbids me from competing for book sales with myself. The only way around that was to wait until several years after that book is available, in early 2016, to publish this one, by which time the 150th anniversary of the Sultana tragedy would be long gone. The other reason, far more pertinent to me, is that I’ve lived with these characters long enough. It’s time to set them and their story free. And to be honest, I have no desire to profit from their suffering.

Download Sultana: The Novel

(three formats available)

PDF | Kindle | iBook

In the coming months, I am hoping to make as much of my research as possible available online through the Johnny Appleseed Education Center & Museum at Urbana University, in Urbana, Ohio — a school with long ties to John Chapman and to the mythic figure he became: Johnny Appleseed.

The URL for the Education Center & Museum is http://appleseed.urbana.edu. Please be patient; the museum is just about to reopen after a major renovation.

For more information, contact Joe D. Besecker, Director of the Johnny Appleseed Society, at jbesecker@urbana.edu or 937.484.1303.

Howard tells All Things Considered host Noah Adams that the real Johnny Appleseed wasn’t much like the slight and sluggish Disney cartoon version.

Chapter 1: Right Fresh from Heaven

Near sunset, one day in mid-March 1845, a seventy-year-old man named John Chapman appeared at the door of a cabin along the banks of the St. Joseph River, a few miles north of Fort Wayne, Indiana. Barefoot, dressed in coarse pantaloons and a coffee sack with holes cut out for his head and arms, Chapman had walked fifteen miles that day through mixed snow and rain to repair a bramble fence that protected one of his orchards. Now, he sought a roof over his head at the home of William Worth and his family—a request readily granted. Chapman had stayed with the Worths before on those few occasions when he felt a need to be out of the weather, a little more than five weeks in all over the previous five-plus years.

Inside, as was his custom, Chapman refused a place at table, taking a bowl of bread and milk by the hearth—or maybe on the chill of the front stoop, staring at the sunset. Accounts vary. The weather might have cleared. Afterward, also a custom, he regaled his hosts with news “right fresh from heaven” in a voice that, one frontier diarist wrote, “rose denunciatory and thrilling, strong and loud as the roar of wind and waves, then soft and soothing as the balmy airs that quivered the morning-glory leaves about his gray beard.”

One version of events has him reciting the Beatitudes, from the Gospel According to St. Matthew: “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are they who mourn, for they shall be comforted. Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth. …” That could be, but for last words—and this was to be his final lucid night on earth—the Beatitudes are almost too perfect, like those morning-glory leaves fluttering in the old gray beard. More likely, Chapman expounded for the gathered Worth family on the “spiritual truths” of the Bible, its hidden codex, a subject for him of inexhaustible fascination.

John Chapman slept on the hearth, by the fire, that night. On that everyone agrees. By morning, a fever had “settled on his lungs,” according to one person present, and rendered him incapable of speech. Within days, perhaps hours, he was dead, a victim of “winter plague,” a catch-all diagnosis that dated back to the Middle Ages and included everything from pneumonia and influenza to the cold-weather rampages of the Black Death. Whatever carried him away, Chapman almost certainly did not suffer. The physician who pronounced him dying later said that he had never seen a man so placid in his final passage. Years afterward, Worth family members would describe the corpse as almost glowing with serenity.

That’s overblown, of course, but with John Chapman—or Johnny Appleseed, as he eventually became known throughout the Old Northwest—just about everything is.

He had paddled into the Ohio wilderness in the opening years of the nineteenth century in two lashed-together canoes, a catamaran of his own design, carrying nothing but a few tools and two sacks stuffed with apple seeds. The land then teemed with danger: wolves, wild boars, and especially black rattlesnakes, known to the pioneers as massasaugas. One of the earliest farmers recorded killing two hundred of them in his first year while clearing a small prairie, roughly one every five yards. Bears, too, were bountiful. In an account of his travels along the Ohio River in 1807–1809, Fortescue Cuming tells of meeting a cattle-and-hog dealer named Buffington, who a few years earlier had killed, along with a partner, 135 black bears in only six weeks—skins had been selling for as much as ten dollars each back then. Yet according to virtually every testimony, Chapman took not a whit of precaution against such wilderness dangers, was heedless of his personal safety, would rather have been bitten by a rattler or mauled by a bear than defend himself against one.

It was a land, too, of rough men and harsh ways. British general Thomas Gage, longtime commander in chief of the Crown’s North American forces, once described the frontier men and women he encountered as “a Sett of People … near as wild as the country they go in, or the People they deal with, and by far more vicious & wicked.”

This was John Chapman’s world. He was part and parcel of it—adrift on the frontier with men and women at the outer edge of American civilization. Yet he appears to have glided over it all: abided by the vicious and wicked, welcomed even by the Native Americans whose land the settlers were seizing, impervious to isolation, without bodily wants or needs. It’s almost as if he drew sustenance from the landscape itself, or maybe he simply absorbed the wilderness and became it, much as he absorbed the myth of Johnny Appleseed and became that, too, in his own lifetime. What the record tells us is that when Chapman was present in whatever setting—a cabin, a town, a clearing—he was a powerful and unavoidable personality. Like many fundamental loners, though, he also was a master of the disappearing act: here one minute, gone the next.

In his 1862 history of Knox County, Ohio, A. Banning Norton calls Chapman/Appleseed “the oddest character in all our history.” That’s a toss-up. The competition for “oddest American [anything]” grows stiffer year by year, but of the many odd characters who populate our early history, John Chapman must count among the most singular of them all—nurseryman; religious zealot; realestate dabbler; medicine man; lord of the open trail, with the stars for a roof and the moon for his night-light; pioneer capitalist; altruist; the list could go on. By tradition, he also seems to have been among the most loved Americans, too. The tributes that followed his death are said to have included this one from Sam Houston, the hero of the War for Texas Independence: “Farewell, dear old eccentric heart. … Generations yet to come shall rise up and call you blessed.”

As we’ll see, there’s more than a little reason to doubt whether Sam Houston ever uttered those words, whether he even knew of Chapman or Appleseed. More likely is this traditional eulogy from another much-lauded fighting man, William Tecumseh Sherman: “Johnny Appleseed’s name will never be forgotten. … We will keep his memory green, and future generations of boys and girls will love him as we, who knew him, have learned to love him.” Sherman had been born and raised in Lancaster, Ohio, land that Chapman was still passing through regularly when the Scourge of the South was yet in his teens. Whether we accept the legitimacy of either eulogy, though, the hope they jointly express has been realized, at best, only in part.

John Chapman did not slip unnoticed into the afterlife. His life and death were summarized in a four-paragraph obituary in the March 22, 1845, edition of the Fort Wayne Sentinel, a lively account that runs to almost three hundred words. But Chapman lies today effectively forgotten on the cutting-room floor of the national narrative—his name almost as likely to evoke John Lennon’s murderer (Mark David Chapman) as it is to bring to mind the true source of that memory Sherman vowed would be ever green.

Johnny Appleseed, of course, does live on, but less as a whole person than as a barometer of the ever-shifting American ideal: by turns a pacifist (extolled by at least one and perhaps two of the most renowned fighting men of the nineteenth century), the White Noble Savage (so remembered long after the Red Savages themselves had been driven from the land), a children’s book simpleton, a frontier bootlegger in the fanciful interpretation of Michael Pollan, patron saint of everything from cannabis to evangelical environmentalism and creation care—everything, that is, but the flesh-and-blood man he really was.

Excerpted from Johnny Appleseed by Howard Means. Copyright 2011 by Howard Means. Excerpted by permission of Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved.

Just a few days after Johnny Appleseed was published, the author had this opportunity to recount some highlights of the life of Johnny Appleseed in this video for C-SPAN2 BookTV at the newly renovated Johnny Appleseed Educational Center and Museum at Urbana University in Urbana, Ohio.